Health

The Fall That Changes Everything: When Seniors Lose Confidence After a Tumble

A fall doesn’t always cause broken bones or head injuries to be life changing. Sometimes the physical damage is minimal, maybe a bruise or two, maybe nothing at all. But something shifts mentally, and that shift can be just as serious as any physical injury. Seniors who were walking confidently one day become hesitant and fearful the next, and that fear creates a whole cascade of problems that families often don’t see coming.

Doctors have a name for this: post-fall syndrome. It’s not an official diagnosis in the medical textbooks, but healthcare providers recognize it as a real and serious condition. After a fall, many seniors develop such intense fear of falling again that they start limiting their activities, moving less, avoiding situations where they feel unsteady. The irony is brutal: the less they move, the weaker they get, and the weaker they get, the more likely they are to fall again.

What Happens in the Mind After a Fall

The psychological impact of falling catches most people off guard. Before the fall, someone might have felt capable and independent. They walked without thinking about it, went where they wanted, didn’t question their body’s ability to keep them upright. Then they fall, and suddenly everything feels different.

That moment of losing control, of suddenly being on the floor with no memory of how they got there, shakes something fundamental. The body that always felt reliable suddenly feels untrustworthy. Every step becomes a conscious decision, every surface looks potentially dangerous, and the confidence that made movement automatic is just gone.

For some seniors, the fear becomes so intense it meets the criteria for a phobia. They might have panic attacks when they need to walk across a room. They might refuse to go outside even though they’re physically capable. The fall becomes a dividing line in their life: before and after, independent and dependent, confident and afraid.

The Physical Consequences of Fear

Here’s where things get complicated. When seniors stop moving because they’re afraid of falling, their bodies deteriorate fast. Muscles weaken within days of reduced activity. Balance gets worse when it’s not practiced regularly. Bones lose density without the stress that weight-bearing activity provides. All of this happens quickly in older adults, much faster than in younger people.

Within a few weeks of significantly reduced activity, someone can lose enough strength and balance that they actually are at higher risk of falling. The fear becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. They were afraid they’d fall again, so they stopped moving, which made them weaker, which made falling more likely. It’s a vicious cycle that can be hard to break once it’s established.

There are also broader health impacts. Reduced activity affects cardiovascular health, increases the risk of blood clots, contributes to depression, and can worsen chronic conditions like diabetes or arthritis. Seniors who become sedentary after falls often end up with multiple new health problems that have nothing to do with the original fall itself.

When Safety Measures Help or Hurt

This is where families face a real dilemma. On one hand, taking precautions after a fall makes sense. Installing grab bars, removing tripping hazards, and having ways to call for help if another fall happens are all reasonable responses. Options such as a help alert for falls can actually reduce anxiety by providing reassurance that help will come quickly if needed, which sometimes gives seniors enough confidence to keep moving.

On the other hand, overprotecting someone can reinforce their fear and helplessness. If family members start hovering constantly, insisting the person not walk without assistance, or restricting activities they’re actually still capable of doing safely, it sends a message: you can’t be trusted to take care of yourself anymore. That message, even when it comes from love and concern, can be devastating to a senior’s sense of competence and independence.

The balance is tricky. Reasonable precautions support independence. Excessive restrictions undermine it. But where that line falls is different for every person and every situation, and families often struggle to figure it out.

The Social Withdrawal Problem

Fear of falling often leads to social isolation, which brings its own set of health risks. Seniors might stop going to social events, church, senior center activities, or visits with friends because they’re worried about navigating unfamiliar environments or being somewhere without easy access to help if they fall.

This withdrawal happens gradually. First they skip one event, then another, and before long they’ve stopped going out entirely. Friends stop calling because the answer is always no. Invitations dry up. The world gets smaller and smaller until it’s just the few rooms in their home where they feel relatively safe.

The health consequences of social isolation are well documented. It increases risk of depression, cognitive decline, and even mortality. Some studies suggest that loneliness and social isolation are as harmful to health as smoking fifteen cigarettes a day. So the fear of falling doesn’t just affect physical mobility, it affects mental health and overall wellbeing in profound ways.

What Actually Helps Rebuild Confidence

Getting confidence back after a fall takes time and usually requires a multifaceted approach. Physical therapy is often the foundation. A good physical therapist doesn’t just work on strength and balance, they also work on confidence. They create situations where the person can practice movement in a safe environment, gradually building trust in their body again.

The exercises start simple and get progressively more challenging. Standing from a chair. Walking a few steps. Navigating around obstacles. Taking stairs. Each successful completion of a task builds a little more confidence. The therapist is there to catch them if needed, but more importantly, to show them that they’re capable of more than they think they are.

Addressing the home environment helps too, but in a thoughtful way. Remove genuine hazards like loose rugs or poor lighting. Add supports where they’re truly needed. But don’t turn the home into a padded room or eliminate every challenge. Movement requires some level of challenge to maintain strength and balance.

The Role of Honest Assessment

Sometimes the fear is completely disproportionate to the actual risk. Someone has one minor fall, lands on carpet in their living room, gets up fine, but develops such intense fear they can barely function. In these cases, the psychological component needs direct attention, possibly including therapy that addresses anxiety and phobia.

Other times, the fear is actually an accurate assessment of real risk. If someone has fallen multiple times, has significant balance problems, or has conditions that make falling more likely, their caution isn’t irrational. In those situations, trying to talk them out of their fear isn’t helpful. Instead, the focus needs to be on making movement safer through appropriate aids, supervision when needed, and real solutions that address the underlying problems.

Finding the Middle Ground

The goal isn’t to eliminate all fear. Some caution after a fall is healthy and appropriate. It makes people more aware of their surroundings, more careful about footwear and lighting, more thoughtful about how they move. That kind of measured caution can actually prevent future falls.

The problem is when fear becomes so overwhelming that it prevents activity altogether. That’s when intervention is needed, not to dismiss the fear as irrational, but to find ways to make movement feel safe enough that the person is willing to try. Physical therapy, home modifications, assistive devices, and sometimes medication for anxiety all play a role.

Recovery of confidence doesn’t mean going back to exactly how things were before the fall. It means finding a new normal where someone can move through their world with appropriate caution but without paralyzing fear. It means accepting that some things might need to be done differently now, while maintaining as much independence as possible. That balance is different for everyone, and finding it requires patience, support, and a willingness to work through both the physical and psychological aftermath of falling.

-

Celebrity1 year ago

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Jennifer Rauchet?: All You Need To Know About Pete Hegseth’s Wife

-

Celebrity1 year ago

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Mindy Jennings?: All You Need To Know About Ken Jennings Wife

-

Celebrity1 year ago

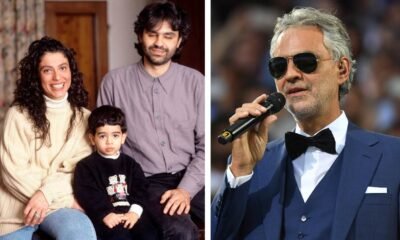

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Enrica Cenzatti?: The Untold Story of Andrea Bocelli’s Ex-Wife

-

Celebrity1 year ago

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Klarissa Munz: The Untold Story of Freddie Highmore’s Wife