Life Style

9 Things Found on Old U.S. Plates

Old U.S. license plates are practical artifacts that double as historical records. Long before standardized designs and reflective coatings, plates carried messages about geography, politics, economics, and everyday life. They were shaped by shortages, state pride, and changing technology, leaving behind clues that still matter to collectors, historians, and drivers curious about the road behind us. This article looks at nine things commonly found on older American plates and explains why each detail existed, what it tells us, and how it still influences the way plates are made and valued today.

Early in the collector market, interest in license plates for sale grew not because of nostalgia alone, but because these objects preserved information no document could fully capture. Fonts, slogans, materials, and even damage patterns reveal how states balanced cost, identity, and enforcement at a particular moment in time. Understanding those details helps explain why old plates look the way they do—and why they remain relevant.

A specialist commentary from ShopLicensePlates reads that when evaluating older plates, condition and originality matter, but context matters just as much. A plate tied to a specific era, material change, or state program often carries more long-term interest than a cleaner but generic example. For readers researching or comparing vintage license plates, understanding what was standard for a given year can prevent overpaying for altered or mismatched items and helps set realistic expectations about availability and value.

State Slogans That Reflected Policy, Not Marketing

Many people associate slogans with modern tourism campaigns, but early plate slogans were usually practical statements tied to policy or governance. States used them to promote infrastructure funding, compliance, or regional unity. Phrases like “Keep Michigan Green” or “Vacationland” came later. Earlier examples were shorter and more direct, sometimes referencing highway programs, agricultural identity, or wartime contributions.

During the 1920s and 1930s, several states experimented with mottos to encourage registration compliance. A clear, bold slogan made a plate easier to recognize from a distance and reminded drivers of civic responsibility. In some cases, slogans aligned with bond initiatives for road construction, subtly reinforcing the idea that registration fees supported better highways.

The language on these plates often mirrored the priorities of the era. Agricultural states emphasized production and land, while industrial states highlighted progress and manufacturing. During World War II, slogans sometimes disappeared altogether as materials were rationed and simplicity became a necessity. Their absence is just as telling as their presence.

From a modern perspective, these slogans provide a snapshot of how states saw themselves and what they wanted drivers to remember every time they got behind the wheel. Unlike today’s branding-driven messages, early slogans were closer to policy footnotes stamped in metal. That utilitarian mindset explains why fonts were blocky, spacing was tight, and decorative elements were minimal.

Materials Shaped by Shortage and Innovation

One of the most striking aspects of old U.S. plates is the variety of materials used. Steel eventually became standard, but before that, states experimented with porcelain-coated steel, aluminum, fiberboard, and even soy-based materials during wartime shortages. Each material choice reflected cost pressures and technological limits.

Porcelain plates from the early 1900s were durable and weather-resistant, but they chipped easily. Once chipped, rust spread quickly, which is why intact porcelain plates are relatively scarce today. Aluminum gained popularity later because it resisted corrosion and was lighter, but during World War II, aluminum was diverted to military use. States responded by issuing plates made from compressed fiberboard or reusing older bases with new validation tabs.

These material shifts affected design. Fiberboard plates required simpler embossing and larger characters to remain legible. Aluminum allowed for cleaner stamping and eventually reflective coatings. The material dictated not only durability but also enforcement effectiveness, since legibility was critical for identification.

Collectors often underestimate how much material affects value and interpretation. A bent aluminum plate from the 1950s tells a different story than a chipped porcelain plate from 1915. Both are authentic, but each represents a different moment in manufacturing capability and resource availability.

Fonts Designed for Enforcement, Not Style

Typography on old plates was chosen for clarity under poor conditions. Before reflective surfaces and standardized lighting, officers needed to read plates in daylight, dust, rain, and darkness. Fonts were tall, narrow, and deeply embossed to cast shadows and remain visible.

Many early plates used state-specific dies, which led to noticeable differences in number shapes. The way a “3” curved or a “1” flared at the base could identify a state even before the name was read. This wasn’t branding in the modern sense; it was a byproduct of local manufacturing contracts and tooling.

Over time, states began to standardize fonts to reduce confusion across borders. Interstate travel increased, and law enforcement agencies pushed for consistency. The gradual move toward uniform typefaces reflects the growing coordination between states and the federal government on transportation issues.

Today’s standardized fonts trace their lineage back to these early experiments. When collectors study old plates, font variations help confirm authenticity and year. A mismatched font often indicates a reproduction or altered plate, which is why typography remains a key detail in evaluation.

Year Markings That Changed with Economics

Year identifiers on old plates varied widely. Some states issued entirely new plates each year, stamping the year directly into the metal. Others reused base plates for several years, adding small metal tabs or corner stamps to indicate renewal. The choice was driven by cost and administrative capacity.

During economic downturns, especially the Great Depression, many states extended plate life to save money. Reusing bases reduced manufacturing costs and allowed registration systems to remain functional with limited budgets. This practice led to multi-year plates with layers of paint or multiple tab holes.

The shift from annual replacement to multi-year systems also affected design complexity. Plates intended for longer use needed more durable finishes and neutral color schemes that wouldn’t clash with future tabs. This practical consideration influenced the move toward simpler, high-contrast designs.

For historians, year markings help map economic stress. Periods with frequent reuse often align with budget shortfalls or material shortages. For collectors, intact original tabs can significantly increase interest because they complete the historical record of how the plate was actually used.

Read More About Tech, Business, and Crypto News at easymagazine

County Codes and Regional Identifiers

Before centralized databases, many states encoded regional information directly onto plates. Numbers or letters identified counties, cities, or registration districts. This helped local law enforcement quickly determine where a vehicle was registered and whether it belonged in the area.

These codes were especially common in large or rural states where travel between regions was less frequent. Seeing an unfamiliar county code could prompt closer scrutiny. Over time, as record-keeping improved and radio communication expanded, the need for visible regional codes diminished.

County coding systems varied widely. Some states placed small prefixes before the main number, while others integrated codes into the numbering sequence itself. The lack of standardization makes decoding old plates a research exercise, often requiring state-specific references.

From a cultural standpoint, county codes reinforced local identity. Drivers could recognize neighbors on the road, and plates subtly signaled regional belonging. As states moved toward anonymity and centralized systems, that local visibility faded.

Paint Layers That Reveal Reuse and Repair

Old plates often carry multiple layers of paint, each one representing a different year or refurbishment. States frequently repainted plates to extend their service life, especially during times of scarcity. These layers can still be seen where paint has worn away.

Paint chemistry evolved over time, moving from lead-based paints to safer formulations. Early paints faded quickly, which is why color shifts are common on surviving plates. Later improvements increased longevity but also made repainting more difficult without stripping the original surface.

For collectors and restorers, paint layers raise important questions. Stripping a plate may improve appearance but erase historical evidence. Many experts prefer conservation over restoration, preserving original finishes even when imperfect.

These layers also tell personal stories. Scratches, touch-ups, and uneven wear suggest how a vehicle was used and maintained. A plate that shows heavy wear on one side may have been mounted slightly crooked for years, a small detail that adds authenticity rather than detracting from it.

Nonstandard Sizes Before Federal Guidelines

Standard plate dimensions were not always a given. Early plates varied in size, shape, and hole placement. Some were taller, others narrower, depending on vehicle design and mounting hardware. It wasn’t until mid-century that federal guidelines pushed toward uniform sizing.

Nonstandard sizes created challenges for manufacturers and drivers alike. Vehicles crossing state lines sometimes needed adapter brackets, and enforcement officers had to adjust expectations about placement and visibility. These inconsistencies eventually prompted calls for standardization.

The move toward uniform size simplified production and enforcement but reduced regional variation. Older plates stand out precisely because they don’t conform to modern expectations. Their dimensions reflect a time when vehicles themselves were less standardized.

For display purposes today, nonstandard sizes can complicate framing or mounting. However, those quirks are part of what makes older plates distinctive artifacts rather than interchangeable decorations.

Validation Methods That Preceded Stickers

Before adhesive stickers became common, states used metal tabs, corner cutouts, or over-stamping to indicate valid registration. Each method had advantages and drawbacks. Metal tabs were durable but costly. Over-stamping saved materials but reduced legibility.

Some states punched holes in specific corners to mark renewal years. Others riveted small plates onto the main base. These methods required officers to know the system in use, adding a layer of complexity to enforcement.

The eventual shift to stickers was driven by cost, ease of distribution, and clarity. Stickers could be color-coded annually and applied quickly. Looking back, earlier methods seem cumbersome, but they worked within the constraints of their time.

Surviving examples with original validation markers intact are especially informative. They show how a plate evolved year by year, not just how it looked when first issued.

Manufacturing Marks and Contract Variations

Many old plates carry subtle marks from the companies that made them. Small symbols, rivet styles, or embossing depth can indicate which contractor produced a batch. States often used multiple manufacturers, leading to slight variations within the same year.

These differences were not intentional design choices but practical outcomes of bidding processes and regional production. Over time, collectors learned to identify these variations, adding another layer to classification and study.

Manufacturing marks help authenticate plates and place them within a broader production context. They also illustrate how decentralized the system once was, with states relying on local industry rather than national suppliers.

Today, when people browse historical license plates for sale, these small details often separate common examples from those with deeper research value. Understanding them turns a decorative object into a documented piece of transportation history.

Old U.S. license plates were never meant to last decades, let alone become study objects. Yet their survival offers a detailed record of how states managed growth, scarcity, and mobility. The nine elements discussed here show that every dent, font choice, and material decision had a reason rooted in its time. Looking closely at these details doesn’t just explain the past; it clarifies how today’s standardized plates came to be and why older ones continue to matter.

-

Celebrity1 year ago

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Jennifer Rauchet?: All You Need To Know About Pete Hegseth’s Wife

-

Celebrity1 year ago

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Mindy Jennings?: All You Need To Know About Ken Jennings Wife

-

Celebrity1 year ago

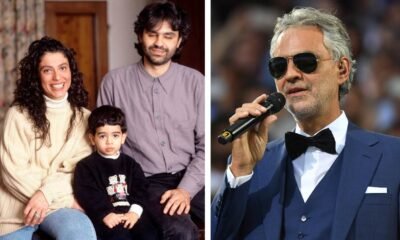

Celebrity1 year agoWho Is Enrica Cenzatti?: The Untold Story of Andrea Bocelli’s Ex-Wife

-

Celebrity2 years ago

Celebrity2 years agoWho Is Klarissa Munz: The Untold Story of Freddie Highmore’s Wife